My Father Xue Mo and I (1)

By Chen Yixin

translated by J. C. Cleary etc.

Part One

From the time I first understood things, I knew that my father was writing a “great book.” I did not think that this writing project would end up taking twenty years. When he first started, he was a young man in the full bloom of youth; when he finished, he was already approaching fifty. Many things happened during the course of writing this “great book,” and now as I think about it, they were interesting indeed.

When we first moved from our native place to a small city, our whole family lived in a studio apartment. The room was very small and just had room for a single bed and a sofa. Later they added a bookcase, and the bookcase took up one wall. Now when I think about it, our life at that time must have been impoverished and difficult. But in my memories it is as if we were the wealthiest and happiest people in the world. At that time, there were no feelings related to “poverty” or “hardship” in my brain, because my father and mother never communicated any information about that to me, and with “arrogance”, I grew up.

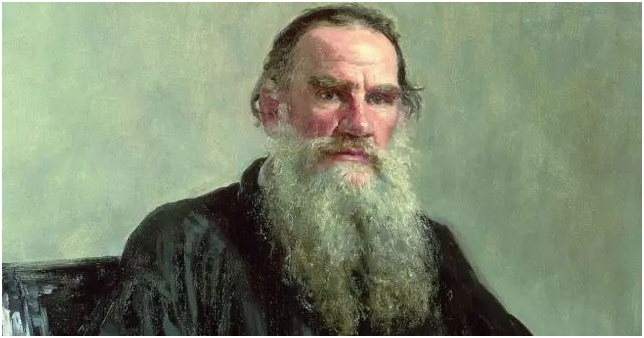

Our whole family was always engaged in lively conversations: we discussed heroes, we discussed love, we discussed history, we discussed success and failure…. When my father was talking about such things with a seven- or eight-year-old child, he did it with all respect and sincerity. He often told me stories of literary people. By the time I went to kindergarten, I already knew the names of many great authors: Tolstoy, Cao Xueqin, Dostoyevsky, Balzac, Victor Hugo…. I was full of yearning for these people. They were like my friends from another time and place, great yet close friends. From that time on, I aspired to be an author, an author like my father. In my mind, he was an author like Tolstoy.

▲ Tolstoy

A lot of the time, we were more like friends. The year I was eight, I questioned my father like this:

“Papa, does eight years count as many years?”

“Eight years? It should be then.”

“Ha! Then from now on the relationship between us is no longer father and son, but elder brother and younger brother!”

“Why?”

“Aren’t you always saying: ‘Over many years, father and son become elder brother and younger brother’? Since eight years counts as many years, we surly are brothers!”

My father laughed. Later, he always told this story to friends.

Every morning my father would get out of bed at 3 a.m. After getting up, he would first sit in meditation, and afterwards he would write. When I opened my eyes, I would always see him looking very energized. Starting from when I was in kindergarten, he insisted that I get up every day at 5 a.m. He would say: “The lamp is lit at three and the cock crows at five, that’s the time a boy studies.” Many people, when they hear that I got out of bed at five in the morning, laugh at my father’s “cruelty,” and are full of sympathy for me. When that happens, I secretly laugh at them: I have three more hours every day than you, and in a year that is a lot of days, and this is equivalent to me living more days than you.

When I was eighteen, I began to try to write a long novel, and I learned from my father to get up at 3 a.m. every day, too. That is the time in my life that is hardest to leave behind. I was totally immersed in a world that I was creating myself, whether happy or sad or love or hate…. I took my soul and transformed it into a cloud, into wind, into snow, into a song, and they were interwoven together, pure and clear and beautiful, expressing the ups and downs of loneliness. Outside the window, the whole was starlight.

As soon as I began to get tired, I would say to myself: “Father can go on this way, and if he can do it, so can I.” It was this thought that helped me persevere through countless difficult predawn sessions. That year, I was still going to school, and I slept less than four hours a day, but it was then that I wrote many pieces that made my father praise me. During that period of time, I felt that my mind and spirit were in connections with my father, because I could always find everything I needed in the expression in his eyes.

Later, I loved getting up early, and my mother said that I loved the feeling that “the whole world is asleep, and I alone am awake.”

When the first draft of my father’s Desert Rites was complete, we moved to an apartment building, and we had a lot of debts. Under these pressures, my father came out of his closed room [where he practiced meditation and wrote], and opened a modest bookstore. When it began to get busy, my father would cultivate practice in the early hours, then write in the morning, then take care of business matters in the afternoon. He later told me that when he was dealing with business in the afternoon, that was his best opportunity to fine-tune his mind. He said that no matter what he was doing, whether walking, standing, sitting, or lying down, he never left his Yidam[1]. He did not use prayer beads, but he could remember all the mantras that he chanted in a day. He always had a pad of stiff paper with him, and on every sheet he was always writing poems from the Tang and Song Dynasties. Whenever he had a little free time, he would take out a piece of paper and memorize the poems. Later he said that most of the poems he learned by heart, he learned this way.

After the bookstore business stabilized, my father again went into “seclusion.” He shaved his head and shaved off his beard, and went into a farmhouse on the outskirts of the city, and began again in secluded retreat. I did not know where his retreat was, and from that time on, I saw very little of him. Besides taking care of the bookstore, my mother brought my father a meal every day. Before this, for four years, my father had cut off contact with the world, and made his own food, and did not ask my mother to bring him food. At that time, what my father left for my mother was endless waiting. When I was in the sixth grade in primary school, I wrote something like this:

I will dare to say that without my mother, the achievements my father has today would not exist. Without my mother, absolutely no one would have seen the book called Desert Rites. For my father’s sake, my mother has paid too much.

Countless evenings and nights, my mother is always bent over at the window, looking out, waiting. I know that my mother is missing my father. My father is somewhere far from the city cultivating practice and writing. He has spent a full four years cut off from the world.

My father has gone. My mother takes responsibility for everything in the household, and maintains this family. She gets up early and goes to sleep at midnight, and is busy rushing around all day on behalf of the family. She does not let my father worry about this, and she lets him stay there writing with his mind at peace.

My father has gone. The house is empty, and there is no longer the sound of laughter as in the past, no longer the warmth. The house has become cold. My mother patiently bears the solitude and loneliness. But my mother is vey strong-willed. She firmly believes that father is certain to become someone glorious. Since he has paid for it, he is sure to get it; since he has ploughed and sown, there is sure to be a rich harvest; since he has made the effort, he is sure to succeed. She supports her husband with all her strength, and she is not afraid of more pain and more fatigue. She is willing to give her all for the sake of her husband.

My mother’s body was originally already weak, but she overcame all difficulties with her startling courage and strong will. To be honest, I truly admire her. She is a strong woman.Every night the house is so deserted and so quiet it is frightening. Without a bit of warmth, the air seems frozen solid. But my mother passes the solitary nights like this, one after another. In the few years that my father has been writing Desert Rites, my mother has aged a lot. In this time, she has been concerned for my father like a kindly mother. Without the pain of this waiting, she would at least be a lot more youthful than she is now. She has been able to do everything that ordinary women cannot do.

During the four years my father was in secluded retreat, my mother seemed to have aged ten years.

Again and again, dusk; again and again, a solitary silhouette.

I remember one time when I had developed a high fever, and for a whole week there was no way to bring it down. My mother was running back and forth between the hospital and our house by herself the whole time. For those several days and nights, my mother could not sleep. She kept applying a towel soaked in cold water to my forehead, to help bring down my fever. She did not tell my father, for fear of disturbing him. But I cannot forget her hair all blown around by the wind, and how utterly lonely she was.

By now, she began look after me the same way that she had looked after my father at first. She helped me complete all the petty tasks of living, to allow me to have more time to write and to read books. She always said she was using her life to conserve the lives of me and my father, and let us have more time to do the things we wanted to do. When she said this, she always appeared matter-of-fact and resolute.

At times, when my inspiration for writing dissolved away and was almost gone, I was very upset. Every time this happened, my mother would say: “How can there be no future prospects for a lad who gets out of bed at 3 a.m. to write?” When I heard this, all the haziness and upsetting feelings in my mind would dissolve away.

Whenever I was writing something, the house was extremely peaceful and quiet. My mother moved around quietly and spoke softly, for fear that any careless sound would scare off my inspiration, which was fragile as a bubble. My mother never actively demanded to see the pieces I had written. Every time I rapturously lectured her on the composition and selection of materials for the novel, what she gave me in return was a satisfied smile and a look of praise and approval.

Giving her support to my father and giving her support to me, without being aware of it, my mother had aged, and was already past forty. The white hair on the top of her head could no longer be avoided, and the wrinkles she had been shy about now covered her forehead. As I write this, I especially want to cry: I do not know how to pay back my mother. All I can do is write well.

Mention my father, and I am filled with pride. Mention my mother, and I am filled with gratitude.

In order to write that “great book” – in my eyes, this great book even includes my father himself – my father gave up what were, in other people’s eyes, many great opportunities. Whether opportunities to rise to official position, or to get rich, he gave them all up. Colleagues laughed at him for being foolish. Relatives worried but could do nothing. As I young man I did not know why, either, but I supported my father’s decisions, just as later on he supported my decisions.

Every day my father was in that dilapidated closed room, meditating, reading books, writing: a day, a month, a year…. One day, after more than ten years, I went to my father’s closed room. It was a small and narrow room, and in it he had only put a single bed and a writing desk. The writing desk was piled with books. That room was like a cave: very dark, very damp, without any windows in the strict sense, just a narrow skylight. My father joked that he was “sitting in a well observing the sky.” On the wall of the room hung a piece of calligraphy that said: “One who can endure loneliness is truly a good fellow. One who does not encounter the jealousy of others is a mediocre person.”

In October 2000, one of my father’s “great books” was finally published. This was Desert Rites. This book was a big hit, not only because the book itself was excellent, but also because everyone was delighted to talk about the author’s spirt of “sharpening a single sword for twelve years.” Many people were very surprised that in this era of impulsive utilitarianism, someone would take twelve years to write a book, while revising it over and over again. But I understood that my father was not only writing a book, he was completing himself, breaking himself up again and again, and rebuilding himself again and again. He used a pen to reshape his spirit and complete his metamorphosis.

Not long after Desert Rites was published, my father sold off the bookstore at a low price, and still had thousands of books left. Several friends in official posts wanted to help him manage this, but my father did not respond: he donated the whole inventory to the children of the farming villages. He again went into seclusion, where he cultivated his Buddhist practice and began writing Desert Hunters, White Tiger Pass and Curse of Xixia.

(To Be Continued...)

[1] In Vajrayana Buddhism, an Ishta-Deva or Ishta-devata (Sanskrit: इष्टदेवता) (Yidam in Tibetan) is a fully enlightened being who is the focus of personal meditation, during a retreat or for Life. (From: http://tibetanbuddhistencyclopedia.com/en/index.php?title=Yidam)